„TALENT IS AS THIN AS A SHEET OF PAPER, EVERYTHING ELSE IS HARD WORK.”

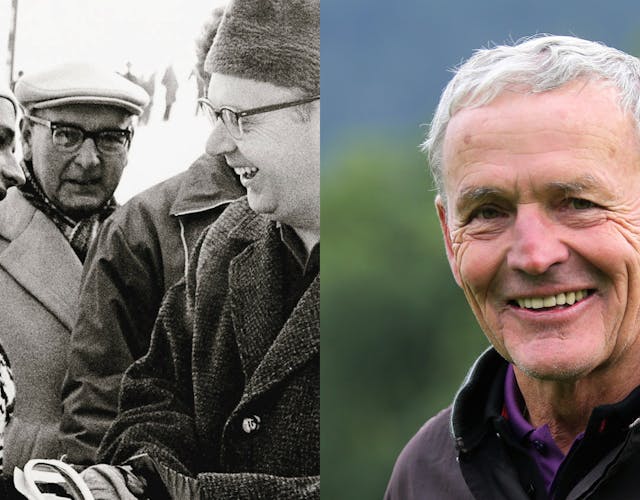

Egon Zimmermann’s successes, most of all the downhill win in the 1964 Olympic Games in Innsbruck, are what make the Fischer brand respectable in racing. The winning ski “Alu Steel” is a must- have. For Zimmermann himself competitive skiing, open only to amateurs in those days, is not particularly lucrative. After a serious car accident in the autumn of 1964 he is unable to repeat his earlier performances. Nevertheless he succeeds again: first as the owner of a Scotch Club and then in charge of the four-star Hotel Kristberg in Lech am Arlberg.

How did you start out with Fischer skis in 1962?

In those days I was with Kästle; but then there was some minor hitch, and I left them. If you want to win, you have to change something, otherwise you have no success. At that point Fischer had the metal ski for downhill. Initially we talked only about the metal ski, but then I said I didn’t want to use this ski from one company and a different ski from another company. So then I took the “S100” wooden ski as well, so as to use only Fischer skis.

What sort of image did Fischer skis have in competitive skiing?

Fischer skis were for the army and the general public. Someone from St. Anton said to me: “Now you’re even using an army ski.” But then I won on the “S100” – the guy from St. Anton was quite taken aback! To start with it counted as an army ski. Then someone wins on it and the ski in question really takes off. But that’s how it is all over: first they laugh at you and then suddenly you’re big time.

What was this winning ski like at the 1964 Olympics in Innsbruck?

In Innsbruck I used a four-channel ski. That was my idea. With the channels the ski sat better for skiing in a straight line. In those days people used skis which were 2.25 m long; the skis I used were 2.28 m long. The channels made the ski calmer in shocks, you lost less speed. But not everyone could handle it. I gave my skis to a friend on the team, he crashed on them right away and never touched a channel ski again. I was also the first skier to use boot liners at that time.

Your greatest success was this gold medal in Innsbruck. What do you recall about the race?

I was World Champion, but the Olympics were the ultimate goal. I had trained well and was fully prepared. I approached the race with the attitude that I simply must win. In those days there were no safety precautions. The course was difficult and dangerous; shortly beforehand there had been a fatal accident in training. My mother had phoned me to say: “Take care!” A mother’s advice is really important, and you are aware of that in such situations. In this race I just wanted to win. That’s exactly how I started off, too. I skied through the trickiest bits in the right way. If you want to win, it’s no good thinking about crashing or playing it safe. At the finish journalists and other people came up to me and said I had won; the Austrian President wanted to congratulate me, too. But I replied: Not now, the race isn’t over yet. Once I had the best time so far and was having a bite to eat when someone came along to say that another skier had actually won. My answer was: Well, then he’s won – I carried on eating, and that was that.

„if you had been speeding, the most the police did was to ask for an autograph.”

How did your life change after this win?

This win didn’t make such a big difference in my case. But then I had a serious car accident in the autumn of 1964. That was really tough for me at that stage – 24 years old and in peak form. It was hard to bear, but I had no choice. In those days we drove cars the same way we skied. That’s why there were so many fatal accidents. Earlier on you had been able to drive differently; if you had been speeding, the most the police did was to ask for an autograph. It was autumn, it had rained a bit – then it doesn’t take much. But we were simply driving too fast. Talk about learning the hard way! The doctor told me that racing would be out of the question in future. However, I wanted to carry on, and started again in the spring. But it just wasn’t the same any more. Then I got allergies and all sorts of things.

How much did you earn as a competitive skier in those days?

In those days we were amateurs pure and simple. The IOC President, Avery Brundage, came to see me because he’d seen a picture of me in an advertisement. I told him I knew nothing about it, and held up three fingers. We weren’t allowed to take anything. If they’d found out that someone had collected 3,000 schillings, he’d have been barred. If you did get anything, it was peanuts. These days it’s a sport in which money plays a central part. The athlete is entitled to earn cash if he’s successful. An athlete who puts more effort into it will always be better. Talent is as thin as a sheet of paper, everything else is hard work.

What were your strong points as a competitive skier?

For me the most important things were always the downhill and the giant slalom. Earlier on I didn’t really bother with slalom, but then I managed some slalom wins too. However, slalom definitely came third for me. If we’d had a ski jump in our area, I’d have become a ski jumper. The further and higher the better! Long drawn-out turns and jumping – that grabbed me. In Megève I was the only one to leap clear over a double bump. That was a dangerous downhill course which is no longer used.

Apart from Olympic gold, what were the highlights in your skiing career?

I became World Champion in Chamonix and won the Olympic title in Innsbruck. Of course it feels great to win important downhill races such as Kitzbühel or Megève. By the time I was 24 I had some impressive results. After the accident everything was quite different.

Which pleasant memories do you have of your days as a competitive skier?

It’s good to have nice friends: fair-minded sportsmen who shake hands with you. I was always on good terms with the French, and with Nenning and Stiegler. That’s something you don’t forget. If you are still in touch today, phone each other up, that’s great. Ingemar Stenmark was a magnificent, fair-minded athlete. His trainer told me that he doesn’t touch alcohol, to which I replied that I do. At some point we then got through two and a half bottles of wine together. In that respect he was no different from anyone else.

What did you do after your career in skiing was over?

I felt I had no future in competitive skiing. Then I made a modest start in Lech, with a Scotch Club with a bar. That went like a bomb. People in politics came, as did royals. It’s fantastic to have contacts like that. If you’re honest to other people, you gain friends. Later I set up Hotel Kristberg in Lech, which a nephew of mine is now running. I’m absolutely delighted with the way he does that. It’s very nice to succeed like that, small scale. And it’s also nice when the guests pay us compliments and ask why we have only four stars. In a hotel there’s always something that needs doing. So whatever should I retire for? If I want to stay healthy, I can’t possibly retire. My health wasn’t too good, which is why I stopped skiing three years ago. I don’t want to hurt myself, because then I wouldn’t be able to move freely in summer. If you want to stay healthy you have to keep moving. Rather than saying “I have aches and pains everywhere”.